A bright and calm day in late September, sandwiched between wet and windy autumnal drear, proved to be a perfect choice for our visit to the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. It was an easy two-hour jaunt by train from the Essex coast, for which supposed hardship we were rewarded by a two-for-one offer on the entrance fee and no waiting in line to get in (cue the Kew queue puns!)

What a day we had! We were treated to some wonderful and at times spectacular examples of plants from around the world, often with interesting stories attached to them. As well as the famous Victorian glass houses and other striking buildings (like Kew Palace) we also spent time around the extensive grounds, which were originally ‘pleasure gardens’ for the royal family. These play host to mature woodlands, ponds and wetlands which in turn support some great wildlife, including numerous badgers and foxes and, for an urban location, an impressive list of birds.

Some corners of the park were described in our guide book as “peaceful and tranquil” – a characteristic it was difficult to locate when every 75 seconds a vast aeroplane taking off from nearby Heathrow roared over the woodland canopy. It says a lot about our priorities as a society, that this monstrous intrusion (undoubtedly with dire implications for the local air quality) is seemingly ignored – and this in (or at least over) a UNESCO-designated World Heritage Site.

An artificial biodiversity

Home to 50,000 plant species over its 120 hectares, Kew claims to be the “most biodiverse place on Earth”. Add to these the 7 million herbarium specimens, and you certainly have the world’s largest collection of plants (living and dead) in any one place on the planet – and from every continent on the planet – though I’m not sure that this is quite what we have in mind when we usually talk about ‘biodiversity’. This quibble aside, it is an astounding place to visit with a marvel at every turn and a wonderful interconnectedness between its multiplicity of exotic trees and plants, on the one hand and, on the other, London’s domestic mundanities such as Canada Geese and Ring-necked Parakeets – appropriately enough two species which themselves originate in opposite corners of the globe.

A 400m length of hedge of native ivy encircling the splendorous Victorian Palm House does provide a shining example of true biodiversity. At two metres high and three metres across, the ivy hedge was elegantly shaped and sculpted looking not the least bit out of place in a formal garden. But it was absolutely lathered with flowers which, with little else flowering at this time of year, were in turn alive with insects. Wasps, honey bees and hoverflies were all in evidence but top billing goes to the vast number of Ivy Bees (Colletes hederae) going about their business.

The bee’s knees

Although now well-established across southern Britain, the Ivy Bee (one of the plasterer bees) is a new arrival to these islands, having been recorded here for the first time less than 25 years ago. Another plasterer bee, the Northern Colletes (Colletes floralis), is a national rarity that we often find on the Coll machair, so it was nice to be reacquainted with its close relative. They’re similar in appearance and habits but the Ivy Bee emerges late in the year (September/October are its months rather than June/July) and is a lot bigger with a lovely golden hue. They have similar nesting habits as well: solitary bees which dig tubular nests in soft earth in which they lay their eggs alongside the nectar they have collected during their forays to often distant flowers – as you might guess, in the case of Ivy Bees they exclusively visit ivy flowers. They line the whole nest with a waterproof membrane of masticated saliva (giving rise to the Colletes genus’s* alternative name of cellophane bees). Although solitary, rather than colonial, they are communal species and, where conditions are right, you can find hundreds of nests alongside each other.

Oaky-dokey

Elsewhere in the grounds we came across an exceptional variety of oak species – who knew there were so many? And how different they all appear! The one thing they had in common was their impressive stature especially the Chestnut-leaved Oak (Quercus castaneifolia), the tallest tree at Kew, and the Lucombe Oak (Quercus x crenata). The latter is a naturally occurring hybrid between Turkey Oak (Q cerris) and Cork Oak (Q suber) both of which are native to the Mediterranean. It is a real curiosity. It was first discovered by a chap called Lucombe at his nursery in Exeter in 1762. He found what he thought was a Turkey Oak sapling which he observed kept its leaves through the winter (like a Cork Oak does). He nurtured it and today all true Lucombe Oaks are clones from this original tree. Lucombe was such a fan that he kept timbers from it under his bed, to be used for his coffin!

A cutting from Lucombe’s original was first planted at Kew in the 1770s. In the 1840s, the royal gardens were gifted to the nation and established as a national botanic garden under the stewardship of renowned Victorian botanist Sir William Hooker. He in turn commissioned the landscape designer William Nesfield to help plan the layout. Now Nesfield was an advocate of the formal ‘vista’, essentially a tree-lined corridor giving views onto a striking feature. At Kew, the Great Pagoda (built in the same year as Lucombe’s discovery) was identified as one such feature and Syon House (just across the river from the gardens) was another. Unfortunately, the (by this time) 70 year-old Lucombe Oak, caught in the middle off the Syon vista, found itself in the wrong place at the wrong time. However, with the typical Victorian spirit of “we can do anything we turn our minds to”, they simply dug it up and moved it to its present location adjacent to the vista where is has continued to thrive ever since.

Today the Lucombe Oak is a massive edifice, with a great burr on one side, perhaps a result of its manhandling nearly 200 years ago. I have to say we enjoyed the view of it far more than that of the lion-topped stately home across the river on whose account it had been moved!

New to science

Meanwhile in the Waterlily House we were treated to the magnificent spectacle of the Bolivian Giant Waterlily (Victoria boliviana) whose rimmed pads grow to over three metres across. The existence of this, the biggest of the giant waterlilies, was only discovered by a team of Kew specialists as recently as 2022, who grew it from seeds shared by a botanic garden in Bolivia. As part of their investigation, they realised that for over 170 years there had been a mis-identified specimen sitting in the herbarium collections waiting to be discovered.

Today the waterlily was accompanied by a large bulbous flower bud whose white petals peeked through the protectively spiked sepals, but as they only open at night, we were not privileged to see the flower in all its glory. There were however, by way of compensation, a great number of impressive and colourful Nymphaea waterlilies and a violet Water Hyacinth alongside the giant pads.

Glasshouses ancient and modern

The famous glasshouses at Kew are a compelling combination of architectural and botanical extravagance. In the cooler Temperate House, we delighted in the number of unfamiliar-looking plants with familiar names – Fuchsias of all shapes and sizes, cabbage-leaved Begonias and the chunky Crassula ovata, like a bonzai Baobab, which bizarrely occupies the same genus as Swamp Stonecrop (Crassula helmsii), a tiny but pernicious weed which swamps many British wetlands.

The Wood’s Cycad growing here tells a sad tale: only one specimen of this plant has ever been discovered in the wild, in a South African forest in 1895. Cuttings were taken and, although the original plant has since died (leaving the species extinct in the wild), it lives on in several botanic gardens around the world. However, there’s a twist: like all cycads, Wood’s Cycad is dioecious, meaning male and female flowers are borne on separate plants. That first (and so far only) wild specimen was male and so all its 100 or so successors, grown from offshoots, suckers and cuttings, are also male. Although it can be cloned in this way over and again, it will never be able to reproduce sexually.

The sweltering atmosphere of the Palm House creates a densely-packed, bewildering riot of greenery with colossal palm fronds metres across, towering banana plants and a thousand other jungle delights flourishing in a vast cathedral of cast-iron and glass. To our surprise we learnt that the different coffee beans you can buy are literally from different species of coffee plant: Coffea arabica and Coffea robusta. Scientists at Kew reckon that a half of the 124 species of Coffea are liable to extinction as a result of climate change and other factors so they are helping to explore other varieties that will be less impacted than these two.

It was fascinating to see Calatheas in something approaching their natural habitat. We usually see them as solitary and often unhappy-looking house plants (under the marketeer’s moniker of Prayer Plants, owing to their habit of folding their leaves together at night); here they were large and healthy and growing abundantly. Unfortunately, the contrast in temperature and humidity between inside and out were a challenge for our camera and most of our photos from the Palm House have a certain fogginess to them!

Next we entered the Princess of Wales Conservatory, a modern computer-controlled glasshouse to experience a series of carefully controlled climatic biomes like a series of mini, rectilinear Eden projects. The spiky cacti in the arid zone looked almost artificial in their perfection. We especially liked the appropriately named Echinocactus grusonii like a giant botanical sea-urchin. Some of the most impressive blooms were in the tropical zone, especially Aristolochia elegans (the Dutchman’s Pipe) and the delicate Episcia cupreata (the Flame Violet – which sounds more like a moth than a plant).

The art of the matter

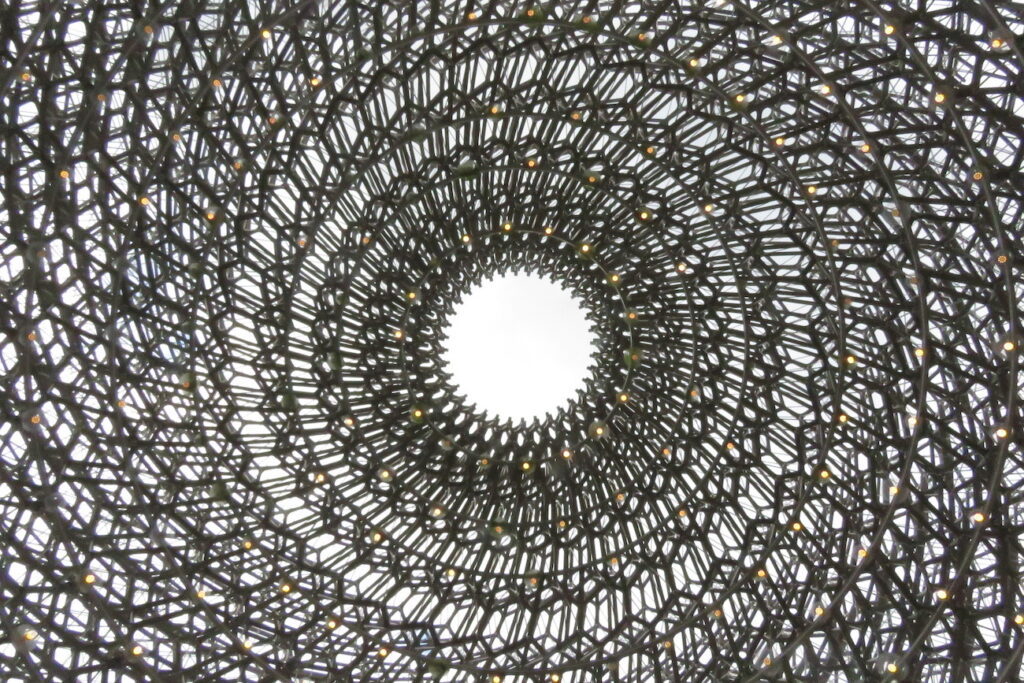

Surrounded by nature’s art, it was interesting to see various examples of human creativity inspired by it, especially The Hive, a vast honeycombed dome of light and sound created by Wolfgang Buttress. Its patterns are literally triggered by the activity of bees in a nearby hive.

Marc Quinn’s various mirror-like, stainless-steel structures of botanical forms were dotted around the gardens. At times it felt like these surfaces formed blank canvasses repeatedly and uniquely completed by the viewer according to where they were standing. The collection of bonsai trees in the Temperate House are also a form of art inspired by, or perhaps harnessed from, nature.

In the end though nothing man-made came close to the beauty and inspirational power of the real thing – today’s WildSmiths Prize went to the trunk of the Fr David’s Maple whose green bark is inscribed with delicate pale longitudinal lines. Incidentally, yes he was the same Fr David (a French missionary to China) who gave his name to Père David’s Deer!

We ended our visit in the gloaming with a pint and a meal at a nearby pub, appropriately named The Botanist on the Green. Suitably fortified, we embarked on the journey home – somewhat less of a jaunt than the journey up, but that’s for another blog!

*Mention of Genesis reminds me that we didn’t see any Giant Hogweed on this visit despite the Royal Gardens at Kew having been the recipient of the first specimen brought home from the Russian hills by a Victorian explorer (pers. comm. Gabriel et al, 1971).